Subscribe

Apple | Spotify | Amazon | iHeart Radio | Player.FM | TuneIn

Castbox | Podurama | Podcast Republic | RSS | Patreon

Podcast Transcript

In the early 1960s, the United States was always a step behind the Soviet Union in the space race.

By the mid-1960s, the Americans had caught up. They didn’t have many glamorous firsts, but they were doing increasingly difficult things in space.

All of that came crashing to a halt on January 27, 1967, when three astronauts died in what was a seemingly routine training exercise.

Learn more about the Apollo 1 Disaster, how it happened, and how it influenced the future of the Apollo program on this episode of Everything Everywhere Daily.

The plan to send astronauts to the moon was announced just three weeks after Alan Shepard’s first flight into space, and the planning had begun well before that.

So, in a very real sense, the entire American manned spaceflight program in the 1960s can be thought of as a build-up to the Apollo program.

The Mercury program was really just a proof of concept that showed that human spaceflight was even possible. Each of the six missions in the Mercury program went a little further. They went from suborbital flights to orbital flights, with the last mission consisting of an astronaut spending a full day in orbit.

Having established that spaceflight was possible, NASA then began the Gemini program.

Gemini was going to be something different. For starters, all of the Gemini flights would have two astronauts in each capsule, not just one as in the Mercury program.

Each mission would test techniques in space which would be a pivotal part of the Apollo program. These included the first space walk, the first docking with a remote vehicle in orbit, the first rendezvous with another manned vehicle in space, the first extended duration flight lasting over a week and then two weeks, and finally, the highest orbit ever achieved by humans.

By the end of the Gemini program in November 1966, they had answered many of the open questions about living and working in space. It was now time to get on to the business of the Apollo program and landing someone on the moon.

As with the Gemini program, there were a host of things that had to be tested before there could be a moon landing. The enormous Saturn V rocket had to be tested as well as the lunar module.

However, the first priority was testing the new Apollo command and Service modules.

The command module was the conical capsule where the astronauts would stay, and the service module was the large cylindrical module attached to the bottom of it, which provided propulsion, fuel cells, oxygen, and water.

All of the other components of the Apollo program depended on the success of these two components.

The first flight of the Apollo program would be an orbital test of the command and service modules. The command module was an early version of Apollo command modules. There was no docking hatch to connect to the lunar module, which for the purpose of this first test, was fine.

The command and service modules were far larger and more complicated than any spacecraft that had ever flown before.

NASA’s plan was to launch this mission, which they had designated AS-204, on February 21, 1967.

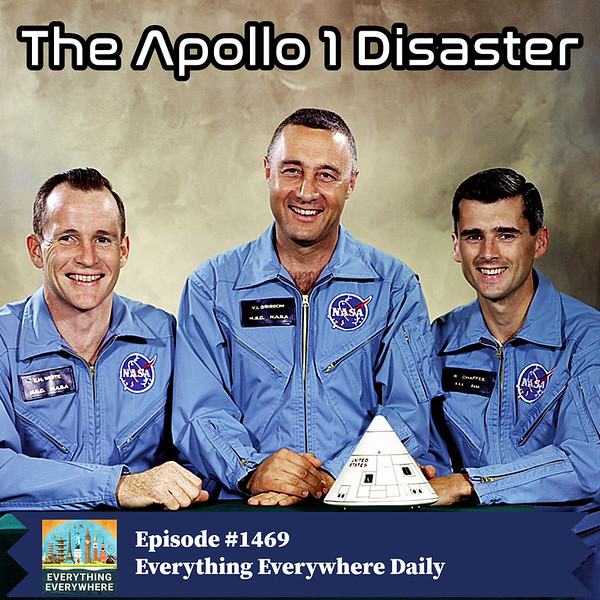

The crew that was selected for this mission was one of the most accomplished and high-profile ones they could have selected.

The Command Pilot was Gus Grissom; Grissom was one of the original Mercury Seven astronauts and was the second American space. His Mercury flight was famous for his capsule sinking.

After the Mercury Program was completed, he was the only member of the Mercury Seven that remained in the astronaut corps. Alan Shepard, another of the Mercury Seven, was technically still on the astronaut roster, but he had been grounded due to being diagnosed with an inner-ear ailment.

Grissom was the commander of the first Gemini mission, Gemini 3, and he was one of the best-known astronauts in the program.

Second in command was another star of the astronaut corps, Senior Pilot Ed White.

White earned his fame by becoming the first American ever to perform a spacewalk.

The third member of the crew was Pilot Roger Chaffee.

Chaffee was a Navy pilot and aeronautical engineer who was selected in the third group of astronauts in 1962.

While NASA designated the flight as AS-204, the crew called it Apollo 1, which certainly rolled off the tongue better.

As part of the preparations for the inaugural Apollo flight, there was extensive testing and training on the ground. This was par for the course for every spaceflight. Every system was tested, and every procedure was thoroughly evaluated.

The Apollo 1 crew was involved with the creation of the command module and worked closely with the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office and the command module manufacturer, North American Aviation.

One of the concerns the crew expressed about the command module was that there was flammable material inside. In particular, nylon netting and velcro inside the command module that were used to hold things in place.

As early as August 1966, there were so many changes that had been made that they had a hard time keeping up with them in the simulator. Gus Grissom took a lemon from a tree at his and hung it on the command module to express his displeasure.

By January 1967, testing and training was entering its final phases. On January 27, the command and service modules were on top of the Saturn-IB rocket on launch pad 34. That day, the crew was scheduled to participate in what is known as a plugs-out test.

A plugs-out test is a test to make sure that the command module can operate when it isn’t connected to any external power sources or umbilical cords.

This was to be a sort of dress rehearsal. The astronauts would be in their space suits, the door of the capsule would be closed, and the atmosphere and pressurization inside the capsule would be the same as during the spaceflight.

Because the Saturn-IB wasn’t fueled, the entire procedure wasn’t considered dangerous.

At 1 pm, the crew entered the capsule in their pressurized spacesuits. After a simulated countdown was stopped, the hatch to the capsule was shut, and the countdown resumed.

With the hatch shut, the capsule was filled with pure oxygen at a pressure of 16.7 psi or 115 kPa, which is higher than that of the atmosphere. The decision to use pure oxygen was to reduce the weight and complexity of a system that used an oxygen/nitrogen mixture.

Pure oxygen had been used in the Mercury and Gemini programs before, and all of those missions went off without incident.

At 6:31 pm, something happened. Cries of “fire” came out from the radio transmissions from the capture. A fire broke out inside the command module, and due to the high-oxygen environment, it spread rapidly. The gases created from combustion were so great that they caused the pressure inside the capsule to spike when it eventually ruptured.

The transmissions from inside the capsule only lasted for five seconds.

Crew members rushed to the capsule, but it took them over five minutes to remove the hatch because of how it was designed. When they eventually did open it, they found that all three crew members were dead.

The heat inside the capsule was so intense that their spacesuits literally melted. Temperatures were estimated to have reached 1000F or 537C.

This was the greatest tragedy in the history of spaceflight at this point. The agency was shocked, and the entire Apollo program was put on hold.

An investigation into the fire was conducted, and they managed to piece together what they believed happened.

The investigation claimed that the fire started when some part of the electrical system had a spark. The spark then ignited a “combustible and corrosive coolant” in a nearby tube.

Because of the high-pressure, pure oxygen atmosphere, the fire spread rapidly. The nylon nets, velcro, and even the astronaut’s spacesuits caught fire in that environment.

When the astronauts tried to escape, they couldn’t because of the design of the hatch. It was complicated to open, and it couldn’t open inward due to the higher pressure inside the command module.

The official cause of death given in the investigation was “cardiac arrest caused by high concentrations of carbon monoxide.” As for the astronauts, they had third-degree burns on a third to a half of their bodies, but it is believed that the burns came after they were already dead.

Up until this point, the Apollo program was on schedule to meet the goal set by President Kennedy of reaching the moon before the end of the decade.

Now, the entire Apollo program was temporarily halted as NASA undertook comprehensive reviews and redesigns of the Apollo spacecraft. These changes were aimed at significantly improving safety protocols and equipment.

They looked at everything in the command and service modules to try to minimize the safety risk to the astronauts.

Several major changes to the spacecraft resulted from the Apollo 1 fire.

For starters, materials used inside the spacecraft were replaced with non-flammable alternatives wherever possible. Also, the cabin atmosphere during ground tests was modified to a nitrogen-oxygen mix, reducing fire risk.

During launches, a nitrogen-oxygen mix was used while the capsule was on the ground, but then it was later replaced with a lower-pressure, all-oxygen atmosphere once it got into space. Likewise, inside the astronaut space suits would still be 100{1eea65b97f16eaff88b6449ec4bd61d0a337087596df763590ffb883bdd967ce} oxygen.

The decision to stick with 100{1eea65b97f16eaff88b6449ec4bd61d0a337087596df763590ffb883bdd967ce} oxygen was, in part, due to the cost and weight of a mixed system, but it was also a concern with astronauts developing decompression sickness or bends.

Nylon in space suits was replaced with a new material known as beta cloth. Beta cloth is made out of a woven silica fiber that is similar to glass fibers.

The hatch was also redesigned so that it would open outward and not have to fight against the air pressure inside the capsule. It could now be opened quickly in the event of an emergency.

Numerous smaller changes were also made, including better insulation of electrical wiring.

Perhaps the biggest change, however, was the change in attitude of everyone working on the Apollo program.

Just three days after the disaster, Gene Kranz, the director of Mission Control, gave a speech to his staff where he said the following:

From this day forward, Flight Control will be known by two words: Tough and Competent. Tough means we are forever accountable for what we do or what we fail to do. We will never again compromise our responsibilities … Competent means we will never take anything for granted … Mission Control will be perfect. When you leave this meeting today, you will go to your office, and the first thing you will do there is to write Tough and Competent on your blackboards. It will never be erased. Each day, when you enter the room, these words will remind you of the price paid by Grissom, White, and Chaffee. These words are the price of admission to the ranks of Mission Control.

The American manned space program was grounded for 20 months until the launch of Apollo 7 in October 1968. The delay gave extra urgency to the program when five missions were launched, Apollo 7 through 11, over the course of nine months.

Gus Grissom and Roger Chaffee were both laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetary, and Ed White was buried at the cemetery at the West Point military academy.

When Apollo 11 landed on the moon, they left behind a medallion with the names of the three crew members from Apollo 1.

Later, after the Apollo Program had ended, Gene Kranz looked back at how the Apollo 1 disaster was a defining moment in the effort to land a human on the moon. He said:

“The ultimate success of Apollo was made possible by the sacrifices of Grissom, White, and Chaffee. The accident profoundly affected everyone in the program. There was an unspoken promise on everyone’s part to the three astronauts that their deaths would not be in vain.”